Safety, Opportunity and Success (SOS) Project

The CJJ “Safety, Opportunity & Success (SOS): Standards of Care for Non-Delinquent Youth,” (“SOS Project”) is a multi-year partnership that engages State Advisory Group (SAG) members, judicial leaders, practitioners, service providers, policymakers, and advocates. The SOS Project aims to guide states in implementing policy and practices that divert status offenders from the courts to family- and community-based systems of care that more effectively meet their needs. The SOS Project also seeks to eliminate the use of locked confinement for status offenders and other non-delinquent youth.

To accomplish this goal, the SOS Project develops tools, resources, and peer leadership to help key stakeholders reform the treatment of youth at risk for and charged with status offenses in their juvenile justice systems. The project builds on more than two decades of CJJ leadership to advance detention reform and promote detention alternatives that better serve court-involved youth, including youth charged with status offenses.

The SOS Project is made possible with the generous support of CJJ’s more than 1,800 members nationwide and the Public Welfare Foundation. For more information, please contact CJJ at 202-467-0864 or [email protected].

Learn more about the SOS Project, as well as information about trainings and media coverage of the SOS Project.

National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses

As part of the SOS Project, CJJ has created the National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses. The National Standards aim to promote best practices for this population, based in research and social service approaches, to better engage and support youth and families in need of assistance. Given what we know, the National Standards call for an absolute prohibition on detention of status offenders and seek to divert them entirely from the delinquency system by promoting the most appropriate services for families and the least restrictive placement options for status offending youth. You can find the full text of the Standards, a list of endorsements, additional content about the issues covered in the Standards, and information about requesting training in the National Standards section of this website. You can read an overview of the National Standards here.

A status offender is a juvenile charged with or adjudicated for conduct that would not, under the law of the jurisdiction in which the offense was committed, be a crime if committed by an adult. The most common examples of status offenses are chronic or persistent truancy, running away, violating curfew laws, or possessing alcohol or tobacco. The National Standards aim to promote best practices for this population, based in research and social service approaches, to better engage and support youth and families in need of assistance. Given what we know, the National Standards call for an absolute prohibition on detention of status offenders and seek to divert them entirely from the delinquency system by promoting the most appropriate services for families and the least restrictive placement options for status offending youth.

The National Standards were developed by the Coalition for Juvenile Justice (CJJ) in partnership with the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) and a team of experts from various jurisdictions, disciplines and perspectives, including juvenile and family court judges, child welfare and juvenile defense attorneys, juvenile corrections and detention administrators, community-based service providers, and practitioners with expertise in responding to gender-specific needs. Many hours were devoted to discussing, debating and constructing a set of ambitious yet implementable standards that are portable, easily understood, and designed to spur and inform state and local policy and practice reforms.

The National Standards build on the original intent of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) and its Deinstitutionalization of Status Offenders core requirement, recent efforts to eliminate the Valid Court Order exception in Congress (S. 3155 and S. 678), and the “safety, permanency and well-being” framework set forth in the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA). Like ASFA’s focus on the child’s best interest, the National Standards call for system responses that keep youth and their families’ best interests at the center of the intervention. Individually and collectively, the National Standards promote system reforms and changes in system culture, as well as the workforce needed to ensure ensures adoption and implementation of empirically-supported policies, programs and practices that effectively meet the needs of youth, their families and the community.

Curriculum

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

Definitions and Key Principles

Judicial Leadership

A growing number of judges in jurisdictions where the VCO exception is allowable are choosing not to securely detain youth alleged to have committed status offenses. Instead, they are leveraging their access and influence to convene practitioners, providers, parents, and other stakeholders to divert youth from the courts and locked confinement and into community-based and family-centered responses that better meet youth and family needs. Like their colleagues in states and jurisdictions that long ago stopped incarcerating youth charged with status offenses, these judges recognize that courts are ill-equipped to independently identify and address the unmet needs that may lead to status-offending behaviors. Building this growing consensus, and the unique influence and access judges have with system actors and policymakers, CJJ identifies and elevates examples of judicial leadership on the use of alternatives to court involvement and detention to address behaviors defined as status offenses. This involves, among other activities, developing profiles of judges who have broken ground in this arena, and distilling the core principles and lessons based on their experiences.

Juvenile and family court judges serve an important role not only in the lives of the youth and families in their courtrooms, but in their larger communities. As part of the SOS Project, CJJ has published several resources on judicial leadership with respect to status offenses.

CJJ published “Making the Case for Status Offense Systems Change: A Toolkit,” a set of resources which give users the tools they need to educate others about status offenses and the need for better responses to youth charged with these behaviors. The materials in this toolkit will help judges and other professionals work with a wide range of audiences, including those who do not have extensive knowledge about status offenses or the court system. Readers can use these tools as an initial step in educating their colleagues and others about the need for improved responses to status offenses.

Status Offense Systems Change Toolkit

Juvenile and family court judges serve an important role not only in the lives of the youth and families in their courtrooms, but in their larger communities. Using their convening power and position as an expert on legal and court issues, judges can educate others about better ways to address the needs of children and families. Other professionals, such as attorneys, juvenile justice agency staff, policymakers and advocates can also raise awareness and share knowledge on these important issues. As part of the Safety, Opportunity and Success (SOS) Project, the Coalition for Juvenile Justice created this “Making the Case for Status Offense Systems Change: A Toolkit,” a set of resources which give users the tools they need to educate others about status offenses and the need for better responses to youth charged with these behaviors.

The materials in this toolkit will help judges and other professionals work with a wide range of audiences, including those who do not have extensive knowledge about status offenses or the court system. The toolkit contains talking points on status offenses, a fact sheet/handout that debunks myths about status offenses, a PowerPoint on improving responses to youth charged with status offenses, a brief on CJJ’s National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses, and additional resources. Readers can use these tools as an initial step in educating their colleagues and others about the need for improved responses to status offenses. Additional materials from CJJ are included in the Appendix to the toolkit, and give more in depth guidance on creating broad and sustainable change.

Judicial Leadership Toolkit

I. Talking Points on Status Offenses

II. Debunking Myths about Status Offenses (Handout)

III. Improving Responses to Youth Charged With Status Offenses (PowerPoint)

IV. The National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged With Status Offenses (Brief)

Appendix

- A. Exercising Judicial Leadership to Reform the Care of Non-Delinquent Youth: A Convenor’s Action Guide for Developing a Multi-Stakeholder Process

- B. Status Offense Laws (Model Policy Guide)

- C. Use of the Valid Court Order Exception in the States (Fact Sheet)

- D. Emerging Issues Briefs

- a. Disproportionate Minority Contact and Status Offenses

- b. Girls, Status Offenses and the Need for a Less Punitive and More Empowering Approach

- c. Running Away: Finding Solutions that Work for Youth and their Communities

- E. Policy Guidance

- a. Addressing Truancy and Other Status Offenses

- b. LGBTQ Youth and Status Offenses

- c. Ungovernable and Runaway Youth

- d. Status Offenses and Family Engagement

- e. Juvenile Defense in Status Offense Cases

- F. POSITIVE POWER: Exercising Judicial Leadership to Prevent Court Involvement and Incarceration of Non-Delinquent Youth

- G. The National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses

CJJ also released, “Exercising Judicial Leadership to Reform the Care of Non-Delinquent Youth: A Convenor’s Action Guide for Developing a Multi-Stakeholder Process,” which offers concrete steps for judicial leaders who want to take action to achieve better outcomes for youth charged with status offenses. The Convener Action Guide shares the experiences of judges across the country who have leveraged their roles on the bench to make a difference in the lives of youth and families in need.

Convener Action Guide

Every day, juvenile court judges bring together a range of family members, attorneys and advocates, service providers, and others to inform decisions in the best interest of youth and to preserve public safety. Judges in many ways are natural convenors in the juvenile justice system. Even so, not all judges have applied and extended their skills outside of the courtroom to bring about system change.

“Exercising Judicial Leadership to Reform the Care of Non-Delinquent Youth: A Convenor’s Action Guide for Developing a Multi-Stakeholder Process” is a tool to support judges seeking to do that work and have that impact. The Convener Action Guide offers concrete steps for judicial leaders who want to take action to achieve better outcomes for youth charged with status offenses. It shares the experiences of judges across the country who have leveraged their roles on the bench to make a difference in the lives of youth and families in need. It translates the lessons from Positive Power into a practical implementation guide for judges interested in effecting change and improving outcomes for non-delinquent youth in their communities.

This guide is written for judges who hear cases or are otherwise responsible for systems that involve youth who were charged with status offenses. It is intended especially for those judges who are looking for ways to play a leadership role and to promote action-oriented discussion in their communities across stakeholder groups that address the needs of these youth.

However, the use of this guide is not restricted to those who believe that confinement of youth charged with non-delinquent behavior is inappropriate. Regardless of a judge’s philosophy on how to address status offenses, the approaches outlined in the guide can still be used to form and sustain meaningful partnerships across stakeholder groups with a unified focus on identifying the best responses to the needs of these youth and their communities.

“POSITIVE POWER: Exercising Judicial Leadership to Prevent Court Involvement and Incarceration of Non-Delinquent Youth” is a brief that profiled nine judges who have worked to improve the lives of children, youth, their families, and communities. These juvenile and family court judges have established alternatives to court involvement and confinement for youth engaged in behaviors identified to the courts as status offenses.

Positive Power

Juvenile and family court judges play a critical role in the lives of youth and families who come into contact with the courts. As part of the SOS Project, CJJ released POSITIVE POWER: Exercising Judicial Leadership to Prevent Court Involvement and Incarceration of Non-Delinquent Youth, a brief that profiled nine judges who have worked to improve the lives of children, youth, their families, and communities. These juvenile and family court judges have established alternatives to court involvement and confinement for youth engaged in behaviors identified to the courts as status offenses. While some changed their approach to status offenses because of legislative mandates, others acted on their own initiative when they realized that confinement was at best ineffective, and at worst harmful to the very children they were seeking to protect. All of these judges are dedicated to ensuring that youth who have unaddressed needs are protected from stigma, marginalization, and exposure to delinquency and criminalization. By diverting them away from the courts and detention, they seek to ensure that vulnerable youth are given access, at home and in their communities, to the resources they need to live healthy, productive lives.

The Honorable Karen Ashby

Denver, Colorado

Judge Karen Ashby was appointed to the bench in 1998 and is the presiding Juvenile Court Judge in Denver, Colorado. The Denver Juvenile Court is a constitutionally separate court from the rest of the state circuit court system with jurisdiction over dependency and neglect, truancy, delinquency, paternity, and child support cases. “In all that I do,” says Judge Ashby, “my goal is to identify what is really best practice, not just what seems reasonable or intuitive or feels good or feels right – particularly in crisis situation.”

The Honorable Joan Byer

Jefferson County, Kentucky

Judge Joan Byer has served as a Circuit Court Judge in the Family Division since 1996. Named Louisville Bar Association Judge of the Year in 2002, Judge Byer has received numerous recognitions as a jurist and community leader. Judge Byer previously served as President of the National Truancy Prevention Association, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the needs of challenged school-aged youth. Among her published articles is “A Model Response to Truancy Prevention: The Louisville Truancy Court Diversion Project,” Juvenile and Family Court Journal, Winter 2003.

The Honorable Frances Doherty

Washoe County, Nevada

Judge Frances Doherty is presiding judge of the Family Court of the Second Judicial District in Washoe County, Nevada. The Second Judicial Family Court has jurisdiction over delinquency cases. Judge Doherty was first appointed a Master with jurisdiction over juvenile delinquency cases in 1997, and elected to the District Court in 2003.

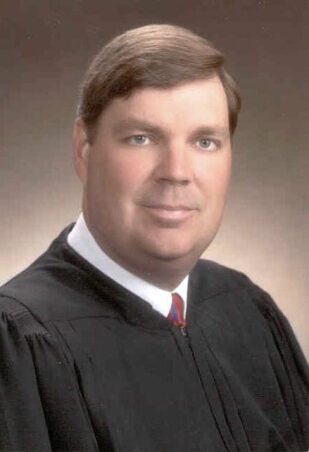

The Honorable J. Brian Huff

Jefferson County, Alabama

Judge Brian Huff is Presiding Judge of the Jefferson County Family Court in Birmingham, Alabama. Judge Huff was appointed to the bench in 2005 and elected to his first full term in 2006. Jefferson County Family Court has jurisdiction over dependency and neglect, delinquency, paternity, and child support cases. Judge Huff presides over several specialized dockets, including Truancy, Juvenile Drug Court, Gun Court, and the Return to Aftercare Program (RAP).

The Honorable Barbara Quinn

State of Connecticut

Judge Barbara Quinn is currently Chief Court Administrator for the State of Connecticut, responsible for the administrative operations of Connecticut’s judicial branch. Prior to this appointment, Judge Quinn served as chief administrative judge for juvenile matters from 2005-2007, where she oversaw the division responsible for hearing Connecticut’s juvenile justice and child protection cases. Prior to that, Judge Quinn was assigned to the Regional Child Protection Session of the Superior Court for Juvenile Matters in Middletown, CT, serving as its presiding judge from 1999-2001.

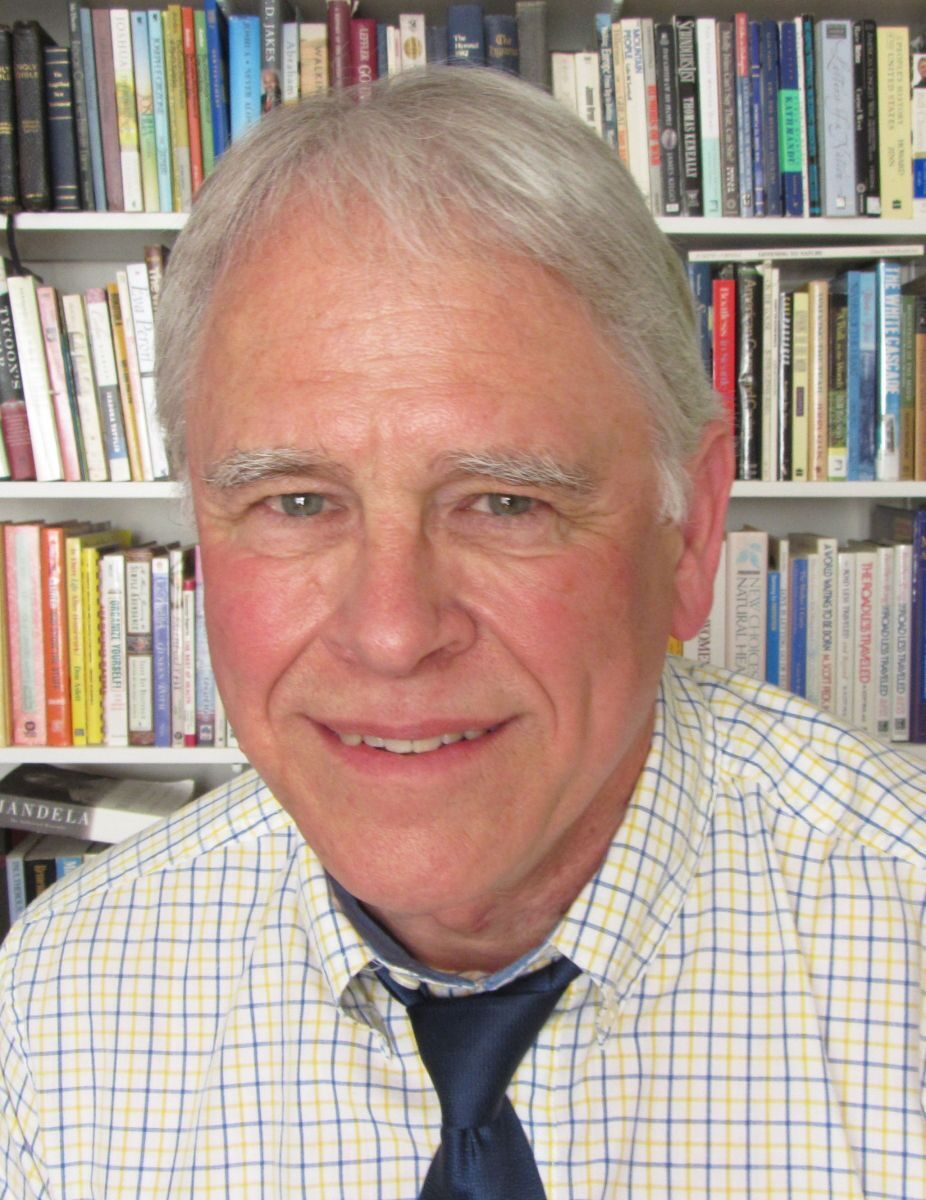

The Honorable David E. Stucki

Stark County, Ohio

Judge David Stucki retired in 2011 as Senior Judge of the Family Court in Stark County, Ohio, where he served for 19 years. The Stark County Family Court has jurisdiction over dependency and neglect, delinquency, paternity and child support cases, as well as juvenile traffic violations. Judge Stucki was first appointed to the family court in 1992 and elected to his first full term in 1994.

The Honorable Steven C. Teske

Clayton County, Georgia

Judge Steve Teske is Chief Judge of the Juvenile Court in Clayton County, Georgia. Judge Teske was appointed to the juvenile bench in 1999 and became Chief Judge in 2009. The Clayton County Juvenile Court has jurisdiction over delinquency, dependency and neglect, paternity and child support cases. “When sitting on the bench or deciding diversion and informal adjustment policies for the court, I look back on my own childhood,” says Judge Teske. “Adolescents sometimes do stupid things, and I did plenty of stupid things as a teenager. But I was never arrested or referred to juvenile court, and today I am a judge.” He adds, “Why is it that most of the cases referred to my court are kids…who were never arrested or referred in my day?”

The Hon. Linda Tucci Teodosio

Summit County, Ohio

Judge Linda Tucci Teodosio is the only juvenile court judge in Summit County, Ohio. She has jurisdiction over dependency and neglect, delinquency and child support cases, as well as juvenile traffic violations. Judge Teodosio was first elected to the municipal court in 1998, and then to the juvenile court in 2003. Summit County does not utilize locked confinement for youth charged with status offenses. In 2010, Judge Teodosio was honored with the Models for Change Champion for Change Award from the MacArthur Foundation.

The Honorable Dennis Yule

Benton-Franklin Counties, Washington

Judge Dennis Yule was appointed to the Washington State Superior Court for the Benton-Franklin Counties in 1986 and re-elected every four years until his retirement in 2009. During his tenure, Judge Yule served as Supervising Judge for the court’s juvenile division, where he was responsible for setting polices and procedures, overseeing three court commissioners dealing with delinquency and dependency cases, and working closely with the juvenile court administrator. Reflecting on his former practice of detaining youth charged with status offenses, Judge Yule says, “I began wondering if I was more a part of the problem than the solution.”

These varied examples illustrate how efforts to deinstitutionalize status offenders can overcome geographic, demographic, and ideological barriers. Four elements of effective judicial leadership emerge:

- Demand for Evidence-Based Approaches. Each judge is determined to change judicial practice in a manner consistent with the best available data of what produces favorable outcomes for youth.

- Balancing of Interests. While each judge is motivated to identify alternatives to detention, they also take preservation and protection of community safety into account.

- Reliance on Partnerships. Each judge recognizes the value of bringing partners together to develop community-based, family-connected continuums of care for youth.

- Use of Judicial Convening Power. Each judge leverages his/her powers to convene and/or participate in cross-system collaborations.

Improving Responses to Youth Charged with Status Offenses: A Training Curriculum

CJJ has created a training curriculum on “Improving Responses to Youth Charged with Status Offenses.” Upon completion of the training, and with the aid of reference materials, participants will understand and be able to effectively advocate for and identify how to implement the principles outlined in the National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses in their jurisdiction. The training curriculum is divided into four parts: an introduction; modules on the first, second, and third sections of the National Standards; and a fact sheet with definitions of common terms used when discussing status offenses.

Model Policy Development

CJJ is also focusing on the identification and development of model state statutes that effectively divert youth and families away from court and confinement, and toward supportive and family- and community-based services. As part of the SOS Project, CJJ released “Status Offense Laws,” a model policy guide. It outlines key areas of consideration for states that are attempting to craft new legislation related to status offenses. It also helps policymakers ensure that they have addressed all relevant issues, from pre-court diversion, to provision of programs and services, and a child’s right to counsel.

About the SOS Project

Background

Since 1974, the Deinstitutionalization of Status Offenders (DSO) core requirement of federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) has prohibited the incarceration of status offenders and non-delinquent youth involved with the courts. This includes young people alleged to be dependent, neglected, or abused. Embracing this requirement, by 1988 states participating in the JJDPA had reduced status detentions by 95%, nationwide. In recent years, however, there has been an increase in detentions among this population, signaling a shift away from deinstitutionalization and toward incarceration to address non-criminal youth behaviors, many of which are tied to troubled home environments and unmet mental health, learning, or other needs.

In 2009, with the support of the Public Welfare Foundation, CJJ completed a national survey of the states and issued a first-of-its-kind report that assessed states’ compliance with the JJDPA. Above most other concerns, states cited challenges to DSO compliance, including judges’ overuse and misuse of the valid court order (VCO) exception to the DSO core requirement. Since 1984, the VCO exception to the DSO core requirement has allowed detention of adjudicated status offenders if they violate a VCO or direct order from the court. Use of the VCO is also exacerbated by a real or perceived lack of effective and readily accessible court and detention alternatives for families and the courts.

These findings affirmed a position ratified by the CJJ Council of SAGs in 2008 that calls for:

1. A phasing out of the VCO exception;

2. Increased federal resources;

3. Supports to help states expand family-connected and community-based

alternatives to detention; and

4. Formal juvenile court processes designed to meet the unique needs of status

offenders and non-delinquent youth.

The CJJ SOS Project is an extension of these efforts, and will help CJJ members, allies, and the states achieve better outcomes for this youth population, their families, and their communities nationwide.

Project Goals

- Identify and educate key stakeholders about policies and practices that divert status offenders and other non-delinquent youth from formal juvenile court involvement;

- Identify and educate key stakeholders about policies and practices that eliminate the use of locked detention for status offenders and other non-delinquent youth; and

- Inform and advocate for local, state, and federal policies and practices to support effective family-connected and community-based continuums of service for status offenders and other non-delinquent youth.

Historical Context

Since the 1970s, local and state courts, as well as state and federal policymakers, have sought to distinguish youth who commit delinquent offenses from youth who commit status offenses. Status offenses are non-delinquent/non-criminal infractions that would not be offenses but for the youth’s status as a minor. This includes running away, failing to attend school (truancy), alcohol or tobacco possession, curfew violations and circumstances where youth are found to be beyond the control of their parent/guardian(s), which some jurisdictions call “ungovernability” or “incorrigibility.”

Status offenses are often symptomatic of underlying personal, familial, community and systemic issues, as well as other, often complex, unmet and unaddressed needs. Issues that underlie status offense allegations are especially acute for minority youth and adolescent girls. 1 Minority youth identified as status offenders are more likely to have their cases formally petitioned to court than similarly-situated white youth. 2 Research also shows that girls accused of status offenses are petitioned to court more often and detained twice as long as boys. 3

If your national or state organization is interested in endorsing the National Standards or partnering with CJJ on blog posts, op eds, or issue briefs on topics covered in the Standards, please contact CJJ at i[email protected].

Until the mid-1970s, it was common for the juvenile delinquency system to handle status offense cases. Therefore, children were subject to all dispositional or probationary options applied to delinquent youth, including incarceration. Concerned about the short and long-term effects of detaining and institutionalizing non-delinquent youth, many states began implementing different social service responses. A handful of states altered their definitions of child neglect or dependency to include status offenses.

In 1974, Congress affirmed and further encouraged state trends toward decriminalizing status offenses by enacting the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) which, among other things, established the Deinstitutionalization of Status Offenders (DSO) core requirement. In keeping with the DSO core requirement, states receiving federal grants under the JJDPA agreed to prohibit the locked placement of youth charged with status offenses and reform their systems so that youth at risk for, or charged with status offenses, and their families would receive family-and community-based services. In the early years of the JJDPA, between 1974 and 1980, the number of court referrals for status offenses decreased 21% and status offender detentions decreased 50%. 4

The lines, however, between the delinquency system and the status offense system remained blurred and judges and court services professionals expressed concerns that apart from locked confinement there were few dispositional options for youth who commit status behaviors. Thus, in 1980, a valid court order (VCO) exception was added to the JJDPA, giving judges the authority to “bootstrap” status offenders into the delinquency system and place them in secure confinement if they violated a valid order of the court, i.e., attend school regularly or be home by a certain time. 5

Today, according to the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), the vast majority of the 56 U.S. states and territories are in compliance with the DSO core requirement, and current detention numbers are drastically fewer than the hundreds of thousands of youth who were detained annually before implementation of the JJDPA. 6 Yet, every year, state and local policies and practice result in the locked detention of thousands of youth charged only with status offenses. In addition, more than half of U.S. states continue to allow use of the VCO exception to detain youth charged with status offenses. 7 OJJDP currently reports approximately 12,000 annual uses of the VCO exception. 8

Almost 20% of detained status offenders and other non-offenders (e.g., youth involved with the child welfare system) are placed in living quarters with youth who have committed murder or manslaughter and 25% are placed in units with felony sex offenders. 10

Research and evidence-based approaches have proven that secure detention of status offenders is ineffective and frequently dangerous. Specifically, research has shown that:

- Detention facilities are often ill-equipped to address the underlying causes of status offenses.

- Detention does not serve as a deterrent to subsequent status-offending and/or delinquent behavior.

- Detained youth are often held in overcrowded, understaffed facilities— environments that can breed violence and exacerbate unmet needs. 9

- Almost 20% of detained status offenders and other non-offenders (e.g., youth involved with the child welfare system) are placed in living quarters with youth who have committed murder or manslaughter and 25% are placed in units with felony sex offenders. 10

- Placing youth who commit status offenses in locked detention facilities jeopardizes their safety and well-being, and may increase the likelihood of delinquent or criminal behavior.

- Removing youth from their families and communities prohibits them from developing the strong social networks and support systems necessary to transition successfully from adolescence to adulthood. 11

Given that states and localities are primarily responsible for achieving the goals of the DSO core requirement, and that there is a well-supported movement to better respond to the unmet and complex needs of children and youth without court involvement or detention, the Coalition for Juvenile Justice joined forces with several national organizations and experts to develop the National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses (“the National Status Offense Standards,” “National Standards” or “Standards”). The Standards aim to promote ]qtip:best practices|, based in research and social service approaches, to better engage and support youth and families in need of assistance. Given what we know, the National Standards call for an absolute prohibition on the detention of status offenders and seek to divert them entirely from the delinquency system by promoting the most appropriate services for families and the least restrictive placement options for status offending youth. The Standards also promote uniform practice and policy across the states, as well as high quality and equitable services and representation for status offending youth and their families.

The National Standards build on the original intent of the JJDPA DSO core requirement, recent efforts to eliminate the VCO exception in Congress, 12 and the “safety, permanency and well-being” framework set forth in the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA). 13 Like ASFA’s focus on the child’s best interest, the Standards call for system responses that keep youth and their families’ best interests at the center of the intervention. Individually and collectively, the Standards promote system reforms and changes in system culture, as well as the workforce needed to ensure adoption and implementation of empirically-supported policies, programs and practices that effectively meet the needs of youth, their families and the community.

“The National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses [is] perhaps the most comprehensive report on the subject to date.”

Hon. Michael Nash

Presiding Judge

Juvenile Court at Los Angeles Superior Court

To capitalize on the value of peer expertise, the National Standards were developed by the Coalition for Juvenile Justice (CJJ) in partnership with the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) and a team of experts from various jurisdictions, disciplines and perspectives, including juvenile and family court judges, child welfare and juvenile defense attorneys, juvenile corrections and detention administrators, community-based service providers, and practitioners with expertise in responding to gender-specific needs (see Acknowledgements for list). Many hours were devoted to discussing, debating and constructing a set of ambitious yet implementable standards that are portable, easily understood, and designed to spur and inform state and local policy and practice reforms. Once drafted, CJJ invited review and input into the initial draft from additional key stakeholders, and secured several partnerships for the purpose of promoting and supporting the Standards’ broad dissemination and implementation plan.

The National Standards aim to inspire and assist individuals responsible for how local and state systems respond on a macro and micro-level to the needs of youth at risk for, or charged with status offenses, and their families. The Standards’ key audiences include policymakers, legislators and systems design professionals, as well as day-to-day decision makers and practitioners working with youth who commit status offenses and their families. These audiences include the following, among others:

- Juvenile and family court judges and magistrates

- State and local court administrators and court personnel

- Case workers and supervisors, case intake workers and probation staff

- Prosecutors

- Attorneys representing status offenders and guardians ad litem

- Juvenile justice and child welfare administrators

- Administrators of public and private residential facilities where status offenders are held

- Public and private nonresidential community-based service providers

- Mental health administrators and professionals

- Educators, school administrators, school boards and guidance counselors

- Runaway and homeless youth program staff

- Law enforcement officers, including school resource officers

- Policymakers, state and local government officials, legislators, and state advisory boards

To help each reader chart a path to implementation of each standard, the National Standards are organized to maximize understanding as follows:

- The Standard to be adopted is articulated in full – “the black letter.”

- The need and underlying argument for the Standard is presented.

- One or more concrete practice or policy actions items are recommended that readers can take to advance and implement the Standard.

1 Arthur, P.J. & Waugh, R. (2009). “Status Offenses and the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act: The Exception Swallowed the Rule.” Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Homeless Youth and the Law. Vol. 7, Issue 2.

2 Puzzanchera, C., Adams, B., & Sarah Hockenberry (2012). Juvenile Court Statistics 2009. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice.

3 Id.

4Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (Fall/Winter 1995). “Deinstitutionalizing Status Offenders: A Record of Progress.” Juvenile Justice, II (2). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

5 Bootstrapping is a practice whereby courts re-label status offenses as delinquent offenses or punish status offending behaviors with punishments otherwise reserved for delinquent youth.

6 Unofficial data provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

7 Hornberger, N. G., (Summer 2010). “Improving Outcomes for Status Offenders in the JJDPA Reauthorization.” Juvenile and Family Justice Today. Reno, NV: National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Available at: http://www.juvjustice.org/media/announcements/announcement_link_156.pdf.

8Id.

9 Holman, B. & Ziedenberg, J. (2006). The Dangers of Detention. Washington, DC: Justice Policy Institute.

10 Sedlak, A. J., & McPherson, K. S. (May 2010). “Conditions of Confinement: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement.” Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice.

11 Nelson, D. (2008). “A Road Map for Juvenile Justice Reform.” 2008 National KIDS COUNT Data Book. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation.

12 S. 3155, The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Reauthorization Act of 2008. Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-110s3155rs/pdf/BILLS-110s3155rs.pdf. S. 678, The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Reauthorization Act of 2009. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111s678rs/pdf/BILLS-111s678rs.pdf.

13 Adoption and Safe Families Act, 42 U.S.C. Section 1305, et. seq. (1997).

Acknowledgments

The development of these Standards was made possible by the generous support of the Public Welfare Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Program, which supports groups working to end the criminalization and over-incarceration of youth in the United States. It has also been supported by the memberships provided to CJJ by the JJDPA State Advisory Groups (SAGs), nationwide. In particular, CJJ would like to thank, Katayoon Majd, Program Officer for Juvenile Justice at the Public Welfare Foundation, for her wise counsel and tireless support of this project. We would also like to thank Jessica Kendall, J.D and Lisa Pilnik, J.D., M.S. of Child & Family Policy Associates, and Tara Andrews, J.D. who were our principal drafters. These Standards and the larger project to which they relate, “Safety, Opportunity & Success (SOS): Standards of Care for Non-Delinquent Youth,” are the products of a fruitful, ongoing partnership with the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges.

The Standards benefited immensely from the expertise and counsel of a multi-disciplinary Panel of Leaders and Partners, composed of service providers, members of the judiciary, law enforcement professionals, researchers and policy experts, who collaborated with CJJ staff. Over a two-year period, the following individuals and their organizations offered guidance and shared their extensive knowledge about the way the juvenile justice system does, can and should work, specifically with regard to youth with unmet needs charged with status offenses. Without the assistance of our Panel of Leaders and Partners listed below, the development, comprehensive review and promulgation of these Standards would not have been possible.

Review Leaders and Partners

Nick Alexander, JD, Fight Crime, Invest in Kids

Tara Andrews, JD, Consultant (formerly of Coalition for Juvenile Justice)

Patricia Arthur, Esq., Consultant

Dane Bolin, Calcasieu Parish Office of Juvenile Justice Services, Lake Charles, LA

Patricia Campie, Ph.D., American Institutes for Research

The Honorable Tim Connors, Washtenaw County Trial Court, Ann Arbor MI

Howard Davidson, J.D., ABA Center on Children and the Law

Nancy Gannon Hornberger, SAY San Diego (formerly of Coalition for Juvenile Justice)

Sharon Harrigfeld, Idaho Department of Juvenile Corrections

The Honorable Jerrauld Jones, 4th Judicial Circuit of Virginia

Jessica Kendall, J.D., Child & Family Policy Associates

Richard Lindahl, Richard Lindahl Consulting

Shawn C. Marsh, Ph.D., National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

The Honorable Melody McCray-Miller, Former Kansas State Representative

Lisa Pilnik, J.D., M.S., Coalition for Juvenile Justice

Lawanda Ravoira, Ph.D., Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center

Annie Salsich, Vera Institute of Justice

Robert Schwartz, Esq., Juvenile Law Center

Kim Selvaggi, TaylorLane Consulting

Casey Trupin, Esq., Children & Youth Project, Columbia Legal Services, Seattle WA

Marie N. Williams, Esq., Coalition for Juvenile Justice

Geoff Wood, Consultant

Other Expert Readers

We are also grateful to the following individuals who provided important guidance and feedback on specific sections of the Standards:

Bernadette E. Brown, JD, National Council on Crime and Delinquency

Angela Irvine, Ph.D., National Council on Crime and Delinquency

The Honorable Chandlee Johnson Kuhn, Family Court of the State of Delaware

Shannon Price Minter Esq., National Center for Lesbian Rights

Lisa H. Thurau, JD, MA Strategies for Youth

Kelly Wells, M.P.A., American Institutes for Research

Endorsements

The following organziations have endorsed the National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses, by affirming that they support the principles that underlie the Standards, as well as the black letter of each Standard. If your State Advisory Group or national, state, or local organization would like to endorse or help disseminate the National Standards please contact CJJ at [email protected].

The American Civil Liberties Union works in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the U.S.

The Blacks in Law Enforcement in America is a national organization of African American Law Enforcement Professionals. They believe in true freedom, justice, equality, fairness, and effectiveness of law enforcement issues, and the effect of those issues upon the total community. As advocates of law enforcement professionals, BLEA establishes continuous training and support.

The DC Juvenile Justice Advisory Group (JJAG) ensures the provision of comprehensive delinquency prevention programs that meet the needs of youth through the collaboration of many local systems with which a youth may interface.

The Equity Project is an initiative to ensure that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth in juvenile delinquency courts are treated with dignity, respect, and fairness.

Futures Without Violence has led the way for ground-breaking education programs, national policy development, professional training programs, and public actions designed to end violence against women, children and families around the world.

GLSEN strives to assure that each member of every school community is valued and respected regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity/expression.

The Human Rights Campaign advocates on behalf of LGBT Americans, mobilizes grassroots actions in diverse communities, invests to elect fair-minded individuals to office and educates the public about LGBT issues.

LUK is a not-for-profit social service agency located in central Massachusetts dedicated to improving the lives of youth and their families. We run a variety of programs and have events happening throughout the year.

Justice Oversight Commission, Nevada’s State Advisory Group, allocates funds to programs and agencies that support the goals and vision of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA).

The Maine Juvenile Justice Advisory Group works to reduce delinquency and youth violence by providing community members with skills, knowledge, and opportunities to support the development of productive and responsible citizens.

The Juvenile Justice Advisory Committee (JJAC) is Mississippi’s state advisory group appointed by the Governor to advise all parts of the State of Mississippi on issues relating to juvenile justice. The MS JJAC’s goals are to assist the State of Mississippi, particularly the Department of Public Safety, in complying with the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act.

MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership (MENTOR) works to fuel the quality and quantity of mentoring relationships for America’s young people and to close the mentoring gap.

The Montana Board of Crime Control (MBCC) is the designated state agency that administers millions of grant dollars dedicated to preventing and addressing crime statewide. MBCC’s mission is to proactively contribute to public safety, crime prevention and victim assistance through planning, policy development, and coordination of the justice system in partnership with citizens, government, and communities.

The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) empowers school psychologists by advancing effective practices to improve students’ learning, behavior, and mental health. NASP’s priorities include: promoting culturally competent practices, diversifying the profession of school psychology, advocating for children, youth, families, and schools, and enhancing professional advocacy.

The National Association of Youth Courts serves as a central point of contact for youth court programs across the nation, delivering training and technical assistance, and developing resource materials on how to enhance the operations of some 1,050 youth court programs in the United States.

The National Center for Lesbian Rights works to advance the civil and human rights of LGBT people and their families through litigation, legislation, policy, and public education.

The National Crittenton Foundation works to advance the self-empowerment, health, economic security and civic engagement of girls and young women impacted by trauma and violence.

The National Juvenile Defender Center works to build the capacity of the juvenile defense bar and to improve access to counsel and quality of representation for children in the justice system.

The National Network for Youth is a membership organization that advocates at the federal level to educate the public and policymakers about the needs of homeless and disconnected youth.

The Parent Teacher Association works to make every child’s potential a reality by engaging and empowering families and communities to advocate for all children. The National PTA comprises millions of families, students, teachers, administrators, and business and community leaders.

The Sayra and Neil Meyerhoff Center for Families, Children and the Courts at the University of Baltimore is a national leader in promoting the concept of a Unified Family Court system to resolve family conflicts in a therapeutic, ecological, and service-based manner.

The Sentencing Project works for a fair and effective U.S. criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing policy, addressing unjust racial disparities and practices, and advocating for alternatives to incarceration.

The Tennessee Commission on Children and Youth advocates to improve the quality of life for children and families and provides leadership and support for child advocates. TCYY works to ensure children in Tennessee are safe, healthy, educated, nurtured and supported, and engaged in activities that provide them opportunities to achieve their fullest potential.

The Trevor Project is is the leading national organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) young people ages 13-24.

The Youth Advocate Programs is committed to providing cost-effective, community-based alternatives to institutional placement through direct service, advocacy, and policy change.

The Youth Law Center works to protect children in the nation’s foster care and justice systems from abuse and secure equitable treatment for children in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems.

What People Are Saying about the National Standards

“I am delighted these standards have come to fruition. They represent an exhaustive and thoughtful effort by the Coalition for Juvenile Justice and allied organizations, and will be of immense help to policy makers and practitioners striving to eliminate the use of detention in status offense cases. These standards are a high quality resource that is long overdue.”

Shawn C. Marsh, Ph.D.

Chief Program Officer – Juvenile Law

National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

“National PTA has been a longtime supporter of policies advocating for the rights of all children including youth involved in the justice system. We believe that children arrested for status offenses are in need of family-focused, school, and community-based interventions, rather than being removed from their homes. We are happy to see the standards’ emphasis on these interventions and their integration of family engagement strategies. We are excited for the release of these evidence-based standards and are committed to promoting their successful implementation.”

Otha Thorton

President

National PTA

“The reasons some youth are more vulnerable to status offenses are often environmental and systemic–causes which can be changed. When nearly 40 percent of runaway and homeless youth identify as LGBT, it is because these youth are much more likely to be thrown out of their family home, simply because of who they are. These Standards of Care provide a framework to help end the vicious cycle that leads vulnerable youth into the school-to-prison pipeline, making dreams for the future possible for all youth, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity, race, socio-economic class, or immigration status.”

Abbe Land

Executive Director and CEO

The Trevor Project

“While juvenile justice professionals almost universally believe in deinstitutionalization of status offenders, our experience is that many systems become mired in crisis responses to family, school and community problems that ultimately result in incarceration and a failure to address underlying problems. The CJJ Standards offer comprehensive advice and support to jurisdictions around the country to move beyond, “But what other choice do we have when a child…fill in the blank?” We are especially gratified at the Standards’ attention to keeping status offenders out of formal juvenile court processing and their strong position that incarceration for any purpose is inappropriate. The Standards will surely help to inspire legislative and policy change around the country.”

Sue Burrell

Staff Attorney

Youth Law Center

“For girls, being detained for a status offense is far too often the first step in their involvement in juvenile justice and to their descent deeper and deeper into the system. The Standards developed by CJJ call much needed attention to the unique needs of girls and identifies important changes that can help to ensure that girls receive the support they need to heal and thrive.“

Jeannette Pai-Espinosa

President

The National Crittenton Foundation

“The National Standards for the Care of Youth Charged with Status Offenses are perhaps the most comprehensive report on the subject to date.”

Hon. Michael Nash

Presiding Judge

Juvenile Court at the Los Angeles Superior Court